New Literacy Skills Required

in the Age of AI and the Direction

of Korean Language Education

A Conversation with Professor Seo Hyuk

of the Department of Korean Language

Education, College of Education,

Ewha Womans University

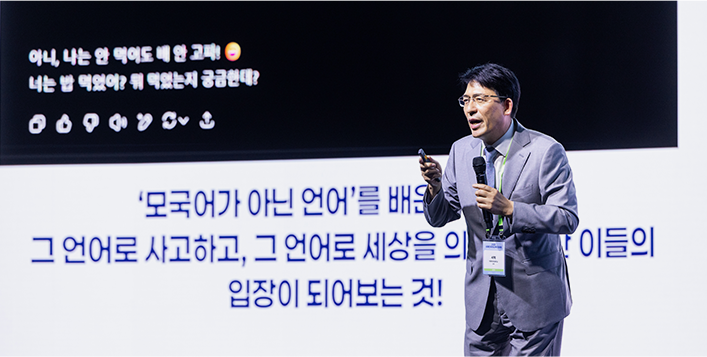

At the opening ceremony of the 2025 World Korean Educator Conference on July 21, Professor Seo Hyuk delivered a keynote lecture on the theme “Literacy in the Age of AI and Korean Language Education.” We spoke with him about the expanded literacy skills required in the AI era and the direction Korean language education should take.

Hello, Professor Seo Hyuk. Thank you for agreeing to this interview. To begin, could you please introduce yourself to the readers of Monthly Knock Knock and tell us about your research and teaching fields?

It’s a pleasure to meet you. I am Seo Hyuk, and I teach and conduct research in the Department of Korean Language Education at Ewha Womans University. My lectures and research mainly focus on literacy, reading education, and reading instruction. In particular, I have paid close attention to the need for scientific and systematic language education, and for over ten years, I have conducted studies on text complexity (readability) and on reading processes using eye-tracking devices. Based on this research, I have worked on textbook development and educational studies. More recently, in response to the advent of the AI era, I have also been conducting research with an interest in AI-assisted language education and literacy education.

Professor Seo Hyuk delivering a keynote lecture at the opening ceremony

of the 2025 World Korean Educator Conference

At the opening ceremony of the 2025 World Korean Educator Conference, you delivered a keynote lecture on “Literacy in the Age of AI and Korean Language Education.” What were the main points you addressed in your lecture?

It was a great honor and a deeply meaningful experience to meet educators from KSIs around the world who are enhancing Korea’s global standing through Korean language education, as I delivered my keynote lecture on “Literacy in the Age of AI and Korean Language Education” at the opening ceremony. In the lecture, I introduced the main themes of my past research and shared key considerations for both teachers and learners regarding expanded literacy in the AI era and the direction Korean language education should take in this context.

First, I presented my earlier research, which includes studies on text complexity (readability) for more scientific and systematic language education, as well as research on the reading process using an eye-tracking device. Of these, my research on text complexity (readability), which I have conducted since 2013, focuses on how to select and provide texts at an appropriate difficulty level that matches the learner’s proficiency. While many readability studies have been conducted abroad, Korean syntax differs significantly from that of Western languages, making it difficult to apply readability formulas or theories developed overseas directly to Korean texts. Therefore, I have studied text complexity using a readability formula that reflects the syntactic and sentence-specific characteristics of the Korean language, and since 2014, I have published the results of this research. Based on these findings, I also collaborated with EBS to develop literacy learning materials. Another study I shared was my research on reading using an eye-tracker, which offers the advantage of quantitatively and visually analyzing and evaluating the specific processes and outcomes of reading, especially the cognitive aspects that are otherwise difficult to observe.

Literacy in the AI era is expanding, deepening, and transforming beyond the simple acts of reading and writing. In particular, the emergence of AI as a new participant in communication creates complex patterns that cannot be explained by existing communication theories. To communicate effectively with AI, one must clearly understand the purpose, participants, and information within the communicative context, and structure messages in a way that AI can accurately interpret.

Furthermore, while communication has traditionally been based on a single mode—speech or writing—in the digital AI era, it encompasses multimodal forms such as images, data, sounds, and videos in addition to spoken and written language. This means that the conventional domains of communication—listening, speaking, reading, and writing—are now being integrated in increasingly diverse and complex ways. In other words, we now live in a communicative context where we must see, hear, and read simultaneously, quickly understand vast amounts of information, and critically evaluate it, all of which place a significant cognitive demand on the individual. I have named this new literacy phenomenon “visual-auditory reading” (bodeul-ilkgi).

Participants listening attentively to the keynote lecture

What are some ways AI tools and technologies can be effectively used in Korean language education to enhance learners’ literacy skills?

A wide variety of teaching and learning tools using AI technology are actively being researched and applied. representative examples include AI chatbot–based conversation practice, vocabulary learning, and reading and writing instruction. More recently, there has been active research into developing programs that use AI for automated scoring or scoring assistance for open-ended assessment items, as well as tools that assist with feedback. In the future, even more advanced educational programs will emerge, and if these are actively utilized, they are expected to be highly beneficial not only for learners but also for teachers.

As teachers well know, classroom hours alone are not sufficient for language education. Learners must make efforts to study and gain experience independently outside the classroom. At such times, AI can serve efficiently as a tutor tailored to the learner’s level and interests. In particular, teachers at KSIs around the world often face challenges in developing textbooks or teaching materials. Preparing for a single one-hour lecture can take several times that amount in preparation, and finding just one suitable example sentence or illustration can sometimes take hours—or even days. In such cases, AI can be extremely useful.

For example, AI can generate a variety of example sentences that match instructional goals, target grammar points, and syntactic patterns. It can also create lesson plans for a single class, a semester, or even a year-long program. Furthermore, AI can provide or suggest various visual and video materials needed for class, as well as organize websites and related research that teachers can refer to.

In this way, AI can generate listening, speaking, reading, and writing materials or assignments that align with teachers’ instructional objectives and learners’ proficiency levels, and it can also produce self-assessment and testing materials for learners. Moreover, AI can create visual aids, images, and videos in the desired format. From my experience, AI does not always produce materials that perfectly match my expectations on the first try. However, it can generate in just a few minutes work that would take hours to create manually, making it extremely useful. In addition, AI can grade students’ writing and provide feedback, which teachers can then use to offer more accurate and constructive feedback to their students.

Professor Seo Hyuk appearing on the EBS educational program Your Literacy

and giving a lecture at a recent special seminar

What new competencies do Korean language teachers at KSIs around the world, as well as other Korean language educators, need in the AI era, and what efforts should they make to acquire them?

I believe AI can be thought of as an “assistant librarian working in a vast information library.” To obtain the resources you want from such a library, you must give precise instructions. In a physical library, users must go directly to the relevant shelves themselves to locate and check out materials, but when you ask AI—as your proxy—to do it, you must clearly instruct it on where to go and what to find.

I call this ability the human QC (Question + Commanding) skill for AI. This is the core of what is now emerging as a new research topic known as Prompt Literacy. In short, to obtain exactly the information you want, you need the ability to structure and present the precise context in which AI can search for, organize, and propose the necessary resources. Of course, even with such input, AI can still produce “hallucinations”—fabricated or inaccurate information—so rather than accepting AI’s outputs as they are, it is necessary to critically compare and verify them through multiple channels and methods.

In the end, to use AI effectively, humans must be smarter than AI. Those who know the direction in which the answer lies are the ones who can obtain the best answers. While AI may operate a vast library of information, it does not fully understand all its contents. Human users are the clients and owners of this vast library, but they cannot—and need not—remember all the information it contains. What we must do is understand AI’s characteristics, strengths, and weaknesses, know precisely when and how to use it, and have the ability to apply it critically. At the same time, it is important not to rely solely on AI, but to maintain a human-driven approach to learning and inquiry.

In this context, AI can serve as a tutor (AI Tutor), but only a human can be a teacher (Human Teacher). This is because the essence of education lies in human-to-human interaction in face-to-face situations, where experiential growth occurs. As educators, we must never lose sight of this.

Lastly, could you share your thoughts on the challenges KSIF should address and the preparations it should make in the rapidly changing Korean language education environment of the AI era?

I understand that KSIF has already made significant efforts, such as developing Korean conversation practice programs using AI chatbots. However, AI technology is advancing at an extraordinary pace, and at its core are large language models (LLMs) built on big data. Recently, not only language data but also various video resources have come to occupy an important place within this big data.

Therefore, I believe it is necessary to collect experiential data from learners and educators across KSIs worldwide. For example, we should gather data on the characteristics and types of Korean language expressions—such as grammar, pronunciation, and writing—as well as examples of errors from learners with different linguistic, sociocultural, and national backgrounds. While some of this data can certainly be obtained from international students studying in Korea, materials collected locally in each country will be far more vivid and representative. Such a large-scale project would require budgetary support as part of KSIF’s mid- to long-term policy and strategic planning.

There is also an approach that could be pursued with relatively modest funding: operating a competition or platform where KSI teachers around the world collect and share exemplary teaching and learning cases using AI. If AI technology is integrated based on such resources, it would be possible to develop highly meaningful AI-based Korean language education programs. We are already living in the AI era—and must also prepare for the post-AI era—so we should actively leverage new AI paradigms to further expand and deepen the excellence of Korean language and culture worldwide.